ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM PT. 2 - THE CLEARCUTTING OF THE REGULATORY FOREST

In my previous article, The Elephant in the Room, I examined the stark reality of Washington State’s housing crisis—where federal and state policies, ostensibly designed to reduce homelessness, have ironically entrenched it. Initiatives like the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness’s (USICH) All In strategy set ambitious goals but failed to deliver measurable results. Similarly, the widely promoted Housing First approach, while rooted in compassionate intent—or at least marketed as such—was implemented without performance-based accountability. The result was skyrocketing homelessness, even as bureaucratic and nonprofit entities profited from an ever-growing flow of taxpayer dollars.

I also exposed how Continuums of Care and the federally mandated Point-in-Time Count inadvertently reinforced a funding model that prioritized management over resolution. The outcomes speak for themselves. Washington’s chronic and unsheltered homelessness has surged far beyond national averages, despite billions poured into programs that consistently fail to deliver.

That article ended with a warning: If state leaders continue to reject deregulation and market-driven solutions, Washington’s housing crisis will deepen.

That was three months ago. Since then, the Trump administration has begun dismantling the very bureaucratic frameworks that have long defined housing and homelessness policy. USICH has been slated for elimination. HUD faces sweeping budget cuts. The Community Development Financial Institutions Fund, a financial pillar of the affordable housing industrial complex, is now on the chopping block.

In short, the regulatory forest is being clear-cut. The question now is whether this aggressive deregulation will stimulate sustainable growth or simply add chaos to an already fractured housing landscape.

This article explores what’s changed, the implications for housing and homelessness policy, and whether this disruption will clear a path for reform or remove the last remaining safeguards in a struggling system.

SECTION 2:

THE EXECUTIVE ORDER THAT ERASED A PILLAR OF HOUSING FINANCE

Most Americans have never heard of Community Development Financial Institutions, or CDFIs. Yet for decades, they served as a financial foundation of the affordable housing industrial complex. That is, until a recent executive order from the Trump administration erased them from the federal budget with the stroke of a pen.

A Seismic Shift in Federal Housing Strategy

The executive order didn’t just shrink HUD or shutter USICH. It went further by targeting the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund—a federal mechanism that funneled billions of taxpayer dollars to politically aligned intermediaries. While HUD and USICH operated in the spotlight, CDFIs worked in the shadows. They didn’t just administer programs; they moved capital, shaped development priorities, and influenced which housing models thrived or failed.

More Than Lenders

CDFIs were presented as mission-driven lenders filling gaps left by traditional banks. In theory, they supported small businesses, community centers, and affordable housing. In practice, they evolved into powerful financial intermediaries with clear ideological preferences—often directing funding toward regulatory-heavy housing models, politically connected nonprofits, and tenant advocacy groups.

• Rent control and rent stabilization

• Eviction moratoria

• Increased regulation of private landlords

• Prioritization of nonprofit developers over private-sector providers

These were not just financial decisions. They shaped policy and market dynamics across cities and states.

The Language Was Clear

The executive order states: “The non-statutory components and functions of the following governmental entities shall be eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law…”

Among the entities named: the CDFI Fund. With that single line, the federal government severed a key artery of funding—one that had long sustained the nonprofit development lobby and institutionalized regulatory preference.

SECTION 3:

CDFIS—THE HIDDEN POWER BEHIND HOUSING POLICY

For decades, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) quietly shaped housing policy, channeling billions through federal programs, private banks, and nonprofit developers. Though largely invisible to the public, CDFIs held significant influence over which housing models were financed and what policies advanced at the state and local levels.

CDFIs were created as mission-driven institutions to finance underserved communities—supporting small businesses, community centers, and affordable housing. Their capital came from federal grants, tax credits, and investments by banks incentivized under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), CDFIs rather than direct engagement with low-income borrowers.

Few in the housing sector fully grasped how deeply embedded CDFIs had become in the regulatory landscape. Their influence was buried beneath layers of bureaucracy and financial complexity, allowing them to shape systems without public scrutiny.

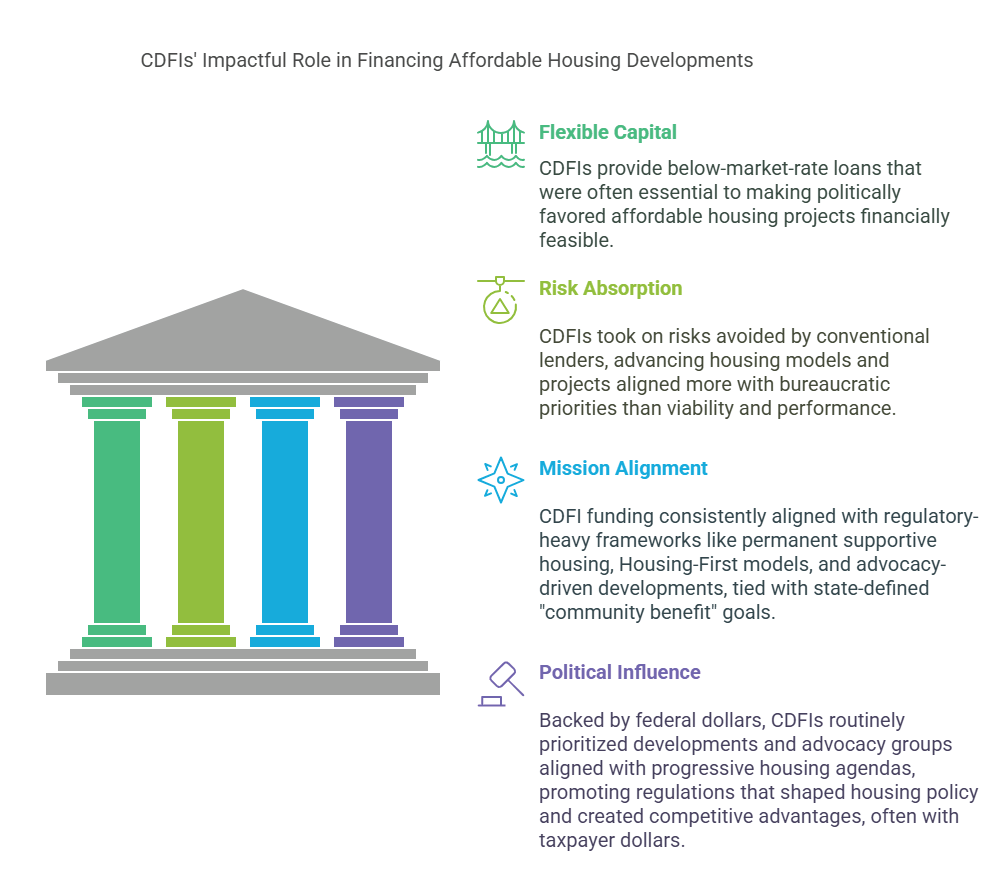

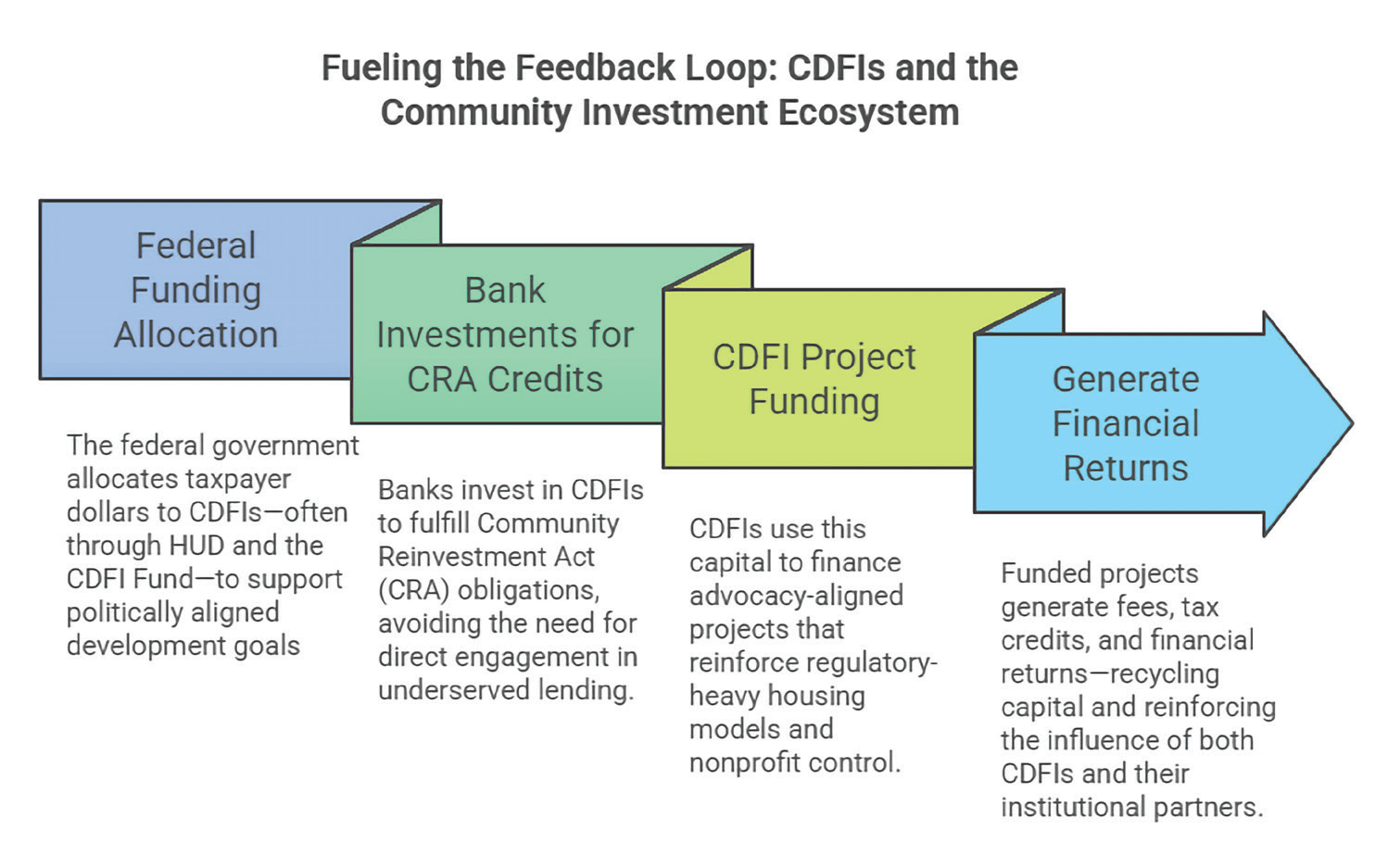

Title: The Role of CDFIs in the Affordable Housing Capital Stack

Caption: CDFIs provided subsidized capital for politically favored housing models, often directing funding toward projects aligned with regulatory and nonprofit priorities.

On paper, CDFIs helped manage risk and attract public-private partnerships. In practice, they reinforced bureaucratic frameworks and rigid funding criteria that often failed to solve homelessness or increase housing supply.

How CDFIs Shaped Housing Policy

1. Controlling Capital, Defining Priorities

CDFIs served as gatekeepers to Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) financing, supportive housing, and nonprofit development capital. Their standards favored tightly regulated models—such as permanent supportive housing or mixed-income projects—while sidelining initiatives outside that mold. Without CDFI-aligned designs, developers often couldn’t secure financing.

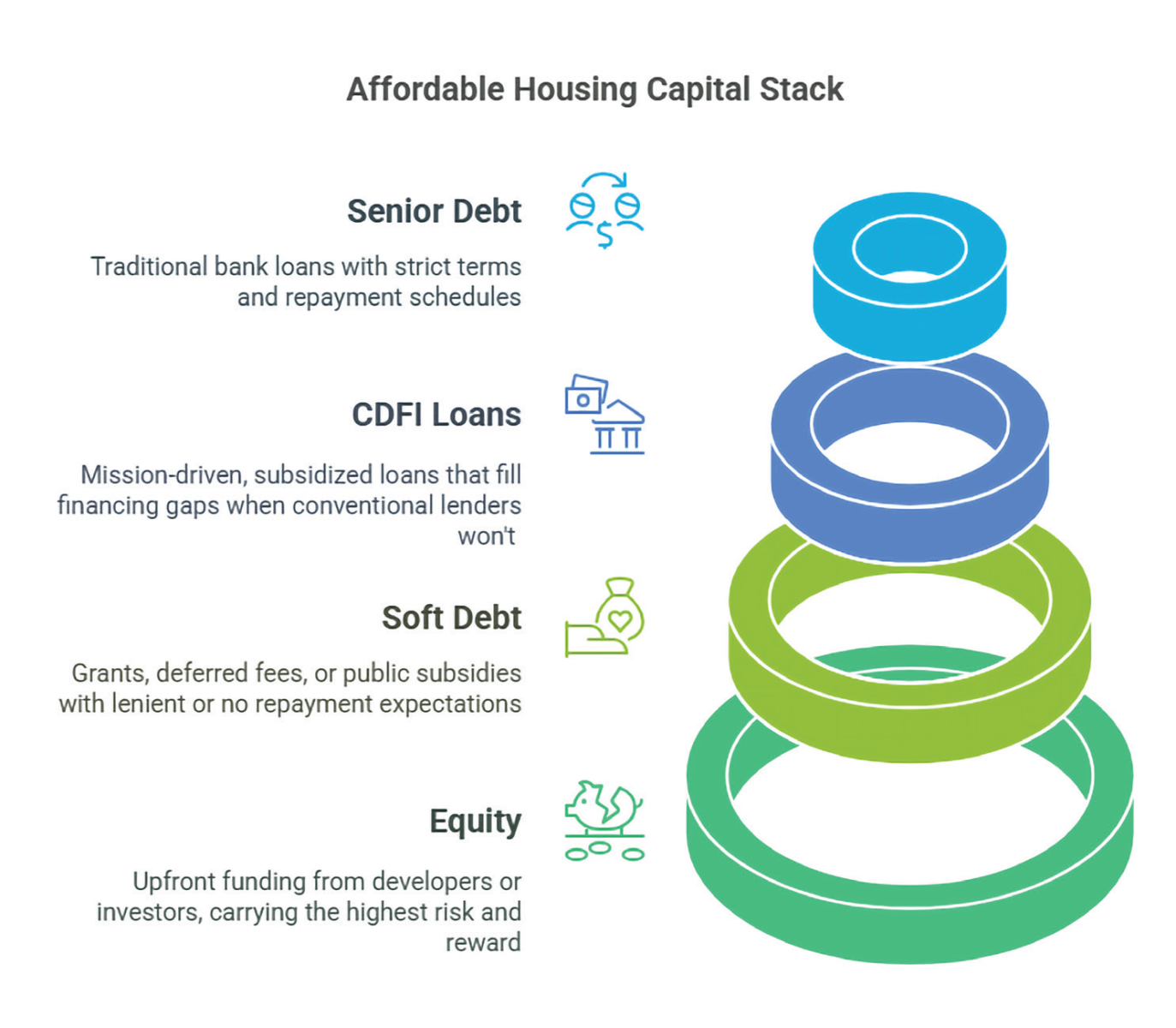

Title: Affordable Housing Capital Stack

Caption: CDFI loans often filled the gap between soft debt and senior debt, becoming essential to making complex capital stacks work in projects dependent on subsidy.

2. Funding Advocacy to Influence Regulation

CDFIs didn’t just fund housing—they funded the politics that shaped it. Many directed capital toward nonprofit advocacy groups lobbying for policies like rent control, eviction moratoria, and increased regulation of private housing providers.

These groups not only influenced legislation but also benefited from the financing structures and exemptions embedded in the policies they helped advance.

A key example is Washington State Senator Emily Alvarado, who also serves as a senior official at Enterprise Community Partners, one of the nation’s largest and most politically active CDFIs. According to its own website, Enterprise engages in affordable housing development, financing, and political advocacy—a rare and potent combination that allows it to influence nearly every phase of the housing ecosystem.

Alvarado herself, as Regional Vice President, oversees Enterprise’s work in Washington and Oregon to “create and preserve affordable homes and bring programmatic solutions to scale through policy advocacy.”

Enterprise has financially supported organizations that advocate for stricter regulation of private housing providers, while simultaneously financing and developing the types of subsidized projects that are often structured to avoid those same constraints.

The rent stabilization bill currently advancing in Washington State, originally sponsored by Alvarado, exempts many forms of income-restricted housing—including properties financed through tools like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), which Enterprise frequently utilizes. While not every LIHTC project is categorically exempt, the bill creates a clear competitive advantage for a class of assets that Enterprise funds, builds, operates, and lobbies for in the legislature. This dual role raises serious ethical concerns and creates the appearance of preferential policymaking.

Meanwhile, Enterprise was receiving millions in federal Section 4 capacity-building grants from HUD. That funding was recently terminated, with HUD citing misalignment with new executive orders. This rare action served as an acknowledgment that taxpayer funds were, at least indirectly, supporting political advocacy through institutional actors.

3. Creating a Financial Feedback Loop Benefitting Bureaucracy

The diagram below explains how CDFIs operated within a self-reinforcing ecosystem—recycling federal dollars, CRA-motivated bank investments, and regulatory influence to fund projects that often prioritized compliance over outcomes.

The result was a funding infrastructure where money flowed from the government to banks, from banks to CDFIs, and from CDFIs to politically favored developers and advocacy organizations. All the while, housing production stagnated and homelessness increased.

What Happens When You Eliminate the CDFI Fund?

The Trump administration’s executive order removed federal support for the CDFI Fund, eliminating its primary capital source. Without taxpayer backing, CDFIs must now rely entirely on private investment or reduce operations significantly.

Key implications:

• Nonprofit developers may face capital shortages, disrupting regulatory-dependent projects

• Advocacy groups may lose funding streams used to influence housing policy

• Banks may be required to reengage directly in affordable housing lending, potentially leading to more performance-based investment

This is more than a bureaucratic change. It is a foundational disruption.

From Collapse to Opportunity

The elimination of the CDFI Fund marks a pivotal moment in housing finance. What fills that space will depend on who steps in and how incentives are structured.

Private capital can pursue returns without apology. In many cases, it succeeds where public systems fail. But when taxpayer dollars are involved—whether through grants, subsidies, or tax credits—transparency, performance, and accountability must follow. No exceptions.

Deregulation may open space for new models focused on housing production, sustainability, and measurable outcomes. But if public subsidies are simply redirected to institutional philanthropy, ESG portfolios, or impact funds without reforming the incentives, we risk rebranding dysfunction instead of fixing it.

These funding streams often partnered with CDFIs and sometimes relied on public pension dollars. With that infrastructure removed, the affordable housing asset class is entering a period of rapid redefinition. Early signs suggest a shift from direct public spending toward tax incentives, which may force these capital sources to realign—less around ideology, more around results.

That’s a conversation for another article. For now, one thing is clear: a central pillar of the affordable housing-industrial complex has collapsed. Whether this leads to genuine reform or a redistribution of influence depends on what happens next and who is paying attention.

If you're in the rental housing industry wondering whether this affects you, it does. If the last article was about selective logging, this one is about the clearcut. What comes next is not theory. It is a legal and political collision with direct consequences for Washington State housing providers.

The trees are coming down. The chainsaws are running. What happens next will decide who is left standing.

SECTION 4:

THE CHAINSAW VS. EVERGREEN STATE

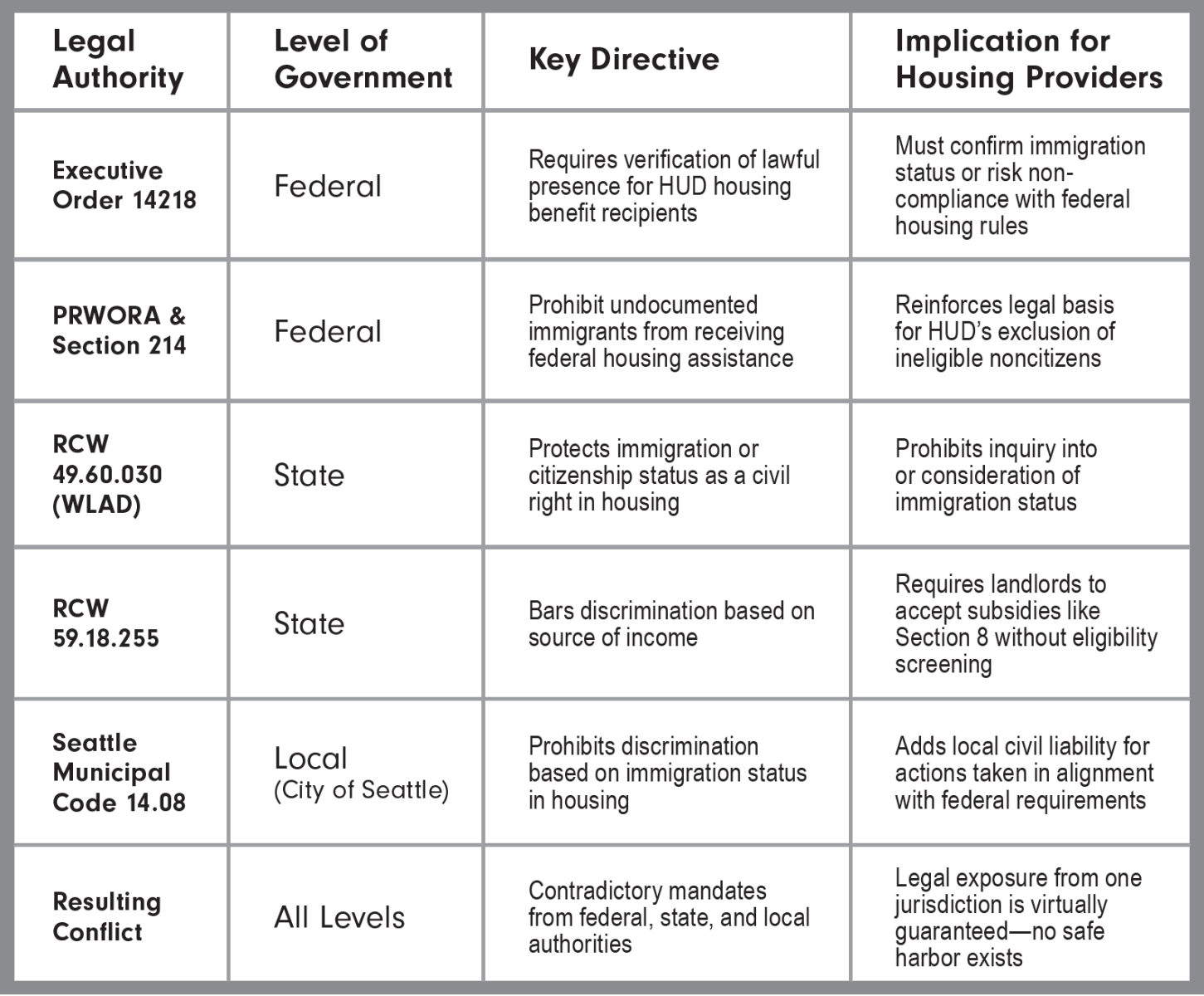

In February 2025, President Trump issued Executive Order 14218—Ending Taxpayer Subsidization of Open Borders—setting the stage for a direct legal clash with Washington State housing law. At its core, the order prohibits undocumented immigrants from receiving federal housing benefits and ties HUD funding to compliance with immigration enforcement.

HUD Secretary Scott Turner quickly followed with a directive revising grant agreements to require screening for lawful presence and warning that sanctuary jurisdictions could lose federal funds. The policy leans on two long-standing but inconsistently enforced statutes:

• PRWORA (1996) – Bars undocumented immigrants from most federal benefits, including housing.

• Section 214 of the Housing and Community Development Act (1980) – Limits HUD assistance to U.S. citizens and legally qualified noncitizens.

These laws had been largely dormant. The executive order brought them roaring back—this time with funding consequences.

Washington State, however, has enacted protections that directly contradict the federal mandate:

• RCW 49.60.030 prohibits housing discrimination based on immigration or citizenship status.

• RCW 59.18.255 bans source-of-income discrimination, requiring landlords to accept vouchers without regard to immigration status.

Cities like Seattle add a third layer. Under Municipal Code 14.08, immigration status is explicitly protected, and housing providers are barred from inquiring about it at all.

The result is a compliance trap. Federal law requires screening. State and local law forbids it. Housing providers face legal exposure no matter which rules they follow.

The table below summarizes this collision:

Federal vs. State vs. Local Law Conflict: Housing Provider Compliance Dilemma

The Sound of Conflict

This legal standoff isn’t theoretical—it’s operational. If a tree falls in the forest and every level of government gives contradictory instructions, does it make a sound? We’re about to find out. The chainsaw is already running.

SECTION 5:

DEFORESTATION – WILL THE CLEARCUTTING OF THE REGULATORY FOREST LEAD TO NEW GROWTH?

The courts may pause some executive actions. But make no mistake: the deforestation of the housing-industrial complex is already underway.

The question is not whether new growth will follow. It is whether we will seize this moment to build something better.

Programs like CDFIs, LIHTC, ESG initiatives, and impact investments are not inherently flawed. When executed well, they can align capital providers, developers, operators, and communities to deliver meaningful outcomes, especially in underserved markets. Despite the disruption caused by recent executive orders, this may not be the end of affordable housing as an asset class. It may be the beginning of something more effective.

The problem emerges when these programs become entangled in cycles of political influence, bureaucratic inertia, and institutional self-preservation. Too often, the funding flows while results remain elusive.

Let us be clear. Property is political. And when billions of taxpayer dollars are at stake, transparency and accountability are not optional. They are obligations.

While entrenched institutions scramble to preserve remnants of the old order, something new is already taking root. The elephant in the room no longer stands by. It now resembles Ganesha, remover of obstacles, holding a Stihl chainsaw. The path is being cleared, perhaps indiscriminately, but cleared nonetheless.

In my next article, I will explore the implications of shifting federal land use, the repositioning of Opportunity Zone investment, and new models of housing production that may shape what grows in this newly opened landscape. With the pending restructuring of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and a redirection of federal priorities, we may be witnessing the most significant reset in housing policy in decades.

Whether this becomes a renaissance or simply a clearing for someone else’s mistakes depends on who picks up the shovel.

References

- Executive Order 14218 – Ending Taxpayer Subsidization of Open Borders (February 2025)

- Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA), Public Law 104-193

- Section 214 of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1980, Public Law 96-399

- RCW 49.60.030 – Washington Law Against Discrimination (WLAD)

- RCW 59.18.255 – Source of Income DiscriminationSeattle Municipal Code Chapter 14.08 – Fair Housing Ordinance

- HUD Announcement (2025) – Termination of Enterprise Community Partners’ Section 4 Capacity Building Grants

- HUD Secretary Scott Turner (April 4, 2025) – Directive on Executive Order 14218 Enforcement