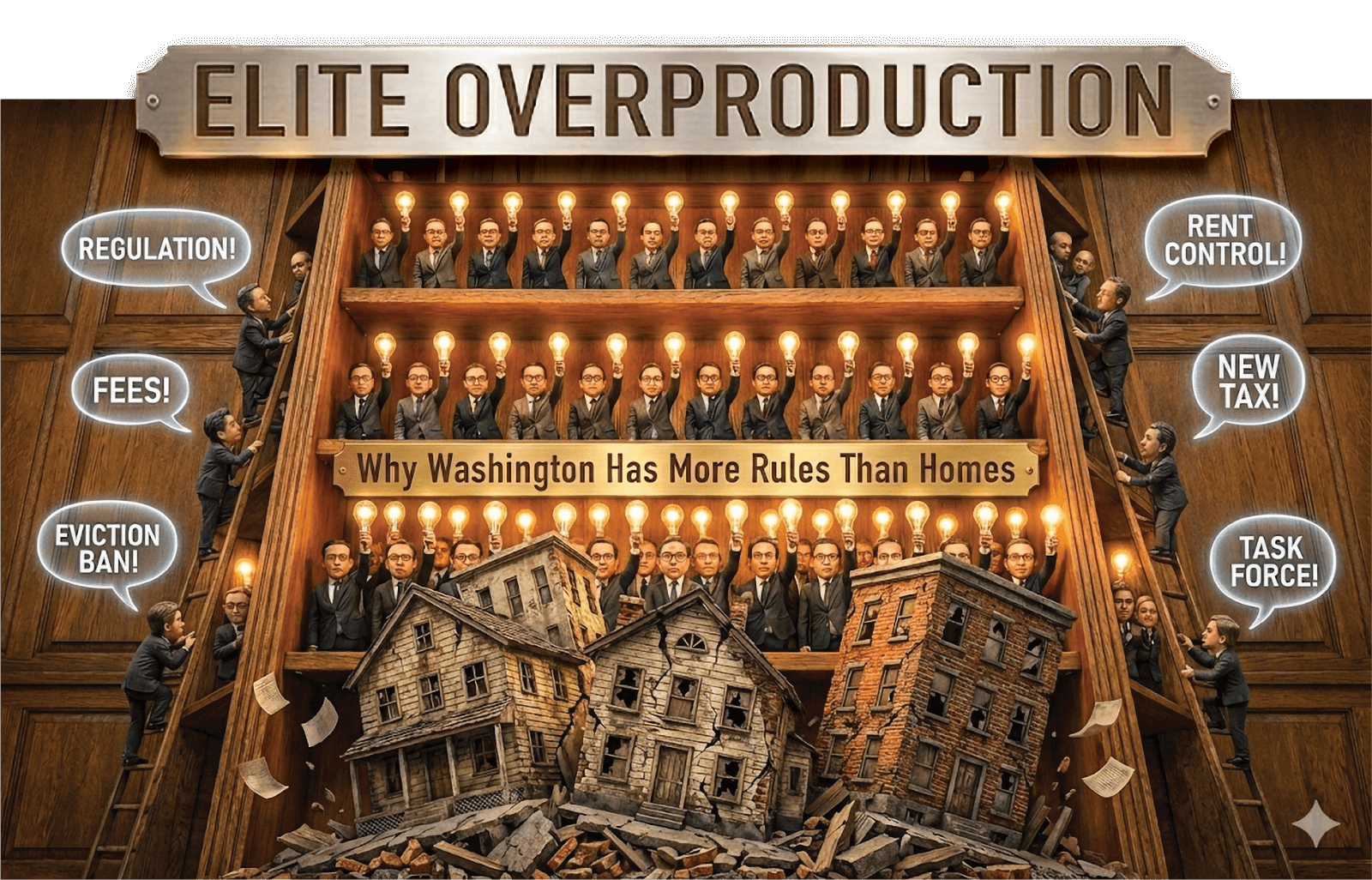

Elite Overproduction

If you have operated rental housing in Washington State for more than five years, you have felt the shift. The issue isn’t only that laws have changed—it’s the cadence. What used to be generational reforms are now seasonal. Every legislative session in Olympia, every city council meeting from Seattle to Spokane, and every local housing committee brings a new wave of notices, forms, registries, and restrictions.

Sit down with a small housing provider today, and the conversation rarely focuses on maintenance or capital planning. It’s dominated by compliance anxiety. Did I use the right font size on the disclosure? Is this jurisdiction currently under an eviction moratorium? Does the new screening ordinance apply to my duplex in the county or just the city? Most providers look at this churning sea of red tape and ask: “Why do they hate us?”

It is a natural emotional reaction, but it is the wrong question. The people writing these laws don't necessarily hate you. They are simply part of a socioeconomic mechanism that has spun out of control.

To understand why Washington produces far more regulations than homes, we have to look beyond politics and examine structure. We have to talk about a concept called “Elite Overproduction.”

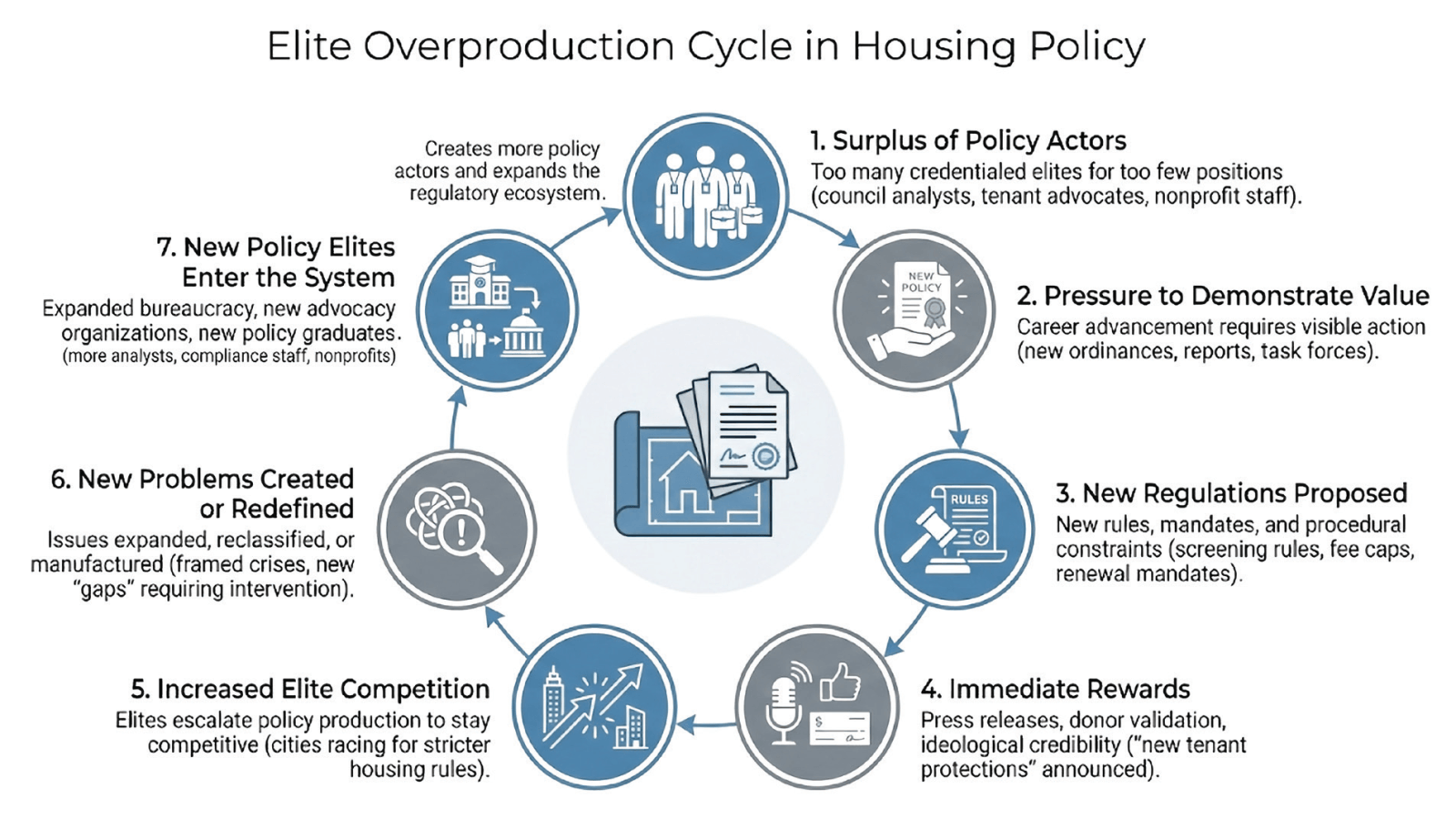

The Mechanism of Elite Overproduction

The term “Elite Overproduction” was popularized by complexity scientist and historian Peter Turchin. While it sounds like a manufacturing term, it describes a social phenomenon.

In any society, there is a demand for “elites”—people in positions of power, influence, administration, and policy-making. We need attorneys, legislators, non-profit directors, and regulatory experts to run a complex civilization.

However, Turchin argues that societies often reach a point where they produce far more credentialed, ambitious potential elites than there are positions for them to fill. We are churning out Juris Doctors, Masters in Public Policy, and Political Science graduates at a record rate.

But here is the catch: The number of seats in the State Senate hasn’t changed. The number of mayorships is static. The number of high-level executive roles in government is finite.

With a surplus of credentialed aspirants competing for a finite number of power centers, competition intensifies. How does an aspiring policymaker stand out? How does a mid-level nonprofit staffer prove value to donors? How does a council aide show they’re ready for the next step?

Not by preserving the status quo. No résumé is built on “The current laws are sufficient.” Advancement requires action.

And in housing policy, “action” almost always means regulation.

This is the core of elite overproduction: an oversupply of professionals whose careers depend on identifying problems and legislating solutions, whether or not new rules are actually needed.

The Washington Laboratory

Washington State, especially the Puget Sound region, has become a textbook example of elite overproduction in housing policy. Over the past twenty years, the number of actors involved in rental housing has exploded:

- Expanded city council staffs with policy analysts

- A proliferation of housing-focused nonprofits and advocacy groups

- Legal aid organizations with growing public funding

- Regional coalitions, task forces, and oversight boards

Each of these entities is staffed by credentialed actors whose career trajectory depends on producing visible policy activity. Budgets, grants, and political relevance all hinge on output. In a factory, output is a widget. In the policy world, output is a rule.

If a tenant advocacy group stops proposing new protections, its urgency and funding fade. If a legislator goes through a session without sponsoring a bill, they appear ineffective.

The result is a policy arms race. To remain relevant, elites push increasingly granular and complex regulations. It is no longer enough to enforce fair housing laws; now we regulate the precise order in which applications are processed. It is not enough to have eviction protocols; we dictate which seasons evictions may occur.

This competition creates a conveyor belt of regulation. The market is not reacting to widespread rental housing provider misconduct; it is absorbing the output of a bloated policy industry.

The Currency of Regulation

For housing providers, the steady stream of rules feels like an assault. But for the policy class, regulation functions as a currency.

This is why so many policies prioritize process over outcome. When a city council passes a Just Cause ordinance or caps move-in fees, they issue a press release and claim a win. The ink on the page becomes the achievement. Whether the policy produces a single new unit or inflates rents by restricting supply is a secondary concern measured years later, if at all. In this environment, simplicity is the enemy. A simple rule, such as “If you do not pay rent, you must move out,” does not require a task force or a legal clinic to interpret.

A complex rule, however, creates job security. Consider Seattle’s First-in-Time ordinance or the RRIO program. These systems require:

- City staff to administer them

- Attorneys to interpret them

- Advocacy groups to monitor them

- Trainers to teach compliance

Complexity becomes self-perpetuating. The more convoluted the regulatory landscape, the more “experts” are needed to navigate it, reinforcing the very ecosystem that created the complexity in the first place.

WHAT MEMBERS ARE SEEING:

The Regulatory Fog

For RHAWA members, this structural dynamic shows up as a very real and expensive problem. The regulatory fog has grown so thick that visibility is almost zero. It appears in three major ways:

- Fragmentation of Rules

State law once handled the fundamentals while cities focused on zoning. Now every jurisdiction is a policy fiefdom. Auburn, Burien, Kenmore, Tacoma, Seattle, Spokane, and Bellingham all have diverging rules on notice periods, late fees, and screening criteria. This fragmentation reflects elite competition, as local leaders try to put their own stamp on policy rather than adopting uniform standards. - A Shift from “Bad Actor” Laws to Universal Mandates

Earlier regulations targeted misconduct, such as shutting off heat. New laws pre-emptively govern business operations for everyone: bans on criminal background checks, mandatory lease renewals, caps on deposits regardless of credit risk. The underlying assumption is that the private sector cannot be trusted to manage housing without administrative oversight. - Administrative Burden as a Feature

The paperwork load—voter registration packets, required font sizes, mandatory information sheets—is not accidental. It creates friction. That friction makes small-scale rental ownership less appealing, conveniently aligning with the goals of policy actors who view housing primarily as a public right rather than a private investment.

THE CONSEQUENCES:

More Rules, No Homes

The tragedy of elite overproduction in housing is that it produces the opposite of its stated goals. Policymakers talk about “stability” and “affordability,” but the result is market constriction.

Increasing the regulatory tax—the cost of compliance, legal risk, and administrative time—changes the economics of the business. For large developers and REITs, this is manageable. They have compliance departments and legal teams. In many cases, they even welcome complex rules because those rules create a moat that keeps smaller competitors out.

For the mom-and-pop provider, the teacher with a duplex or the retiree with a fourplex, this environment is toxic. They operate on thin margins and limited time. When a simple non-renewal requires a lawyer and months of lead time, the risk outweighs the reward.

CONCLUSION:

A Structural Problem Requires a Structural Shift

Understanding elite overproduction is clarifying. It shows housing providers that the chaos they face isn’t personal or accidental—it is the predictable output of a system functioning exactly as designed.

As long as success is measured by the number of bills passed, task forces launched, and restrictions enacted, the machine will keep producing rules. Activity will continue to be rewarded over outcomes.

The solution is a change in metrics. We must stop rewarding the input—regulation—and start rewarding the output: keys in hands and homes built.

For RHAWA members, attorneys, and industry leaders, this means shifting our advocacy. We cannot fight every ordinance one at a time; we must expose the cumulative cost of complexity and hold policymakers accountable for the operational reality they create, not the intentions they advertise.

Washington needs fewer architects of regulation and more builders of housing. Policymakers need a pause on new “good ideas” until the market can absorb the ones already imposed.

Until incentives are realigned with the economics of housing, we will remain stuck in the same cycle: a surplus of rules, a shortage of homes, and a system that grows louder, busier, and less effective every year.